Management of Infants Born to People With HIV Infection

Antiretroviral Management of Infants With In Utero, Intrapartum, or Breastfeeding Exposure to HIV

| Panel's Recommendations |

|---|

Antiretroviral Management for Infants With Exposure to HIV During the In Utero and Intrapartum Periods

Antiretroviral Management for Infants With Exposure to HIV During the Breastfeedinga Period

Recommendations for Infant Antiretroviral Management When the Breastfeeding Parent Experiences New Viremia

Infant ARV Management When a Parent Is Diagnosed With HIV During Breastfeeding

Providers with questions about ARV management of perinatal HIV exposure or exposure to HIV during breastfeeding should consult an expert in pediatric HIV infection or the National Perinatal HIV Hotline (1-888-448-8765), which provides free clinical consultation on all aspects of perinatal HIV, including newborn care (AIII). |

| Rating of Recommendations: A = Strong; B = Moderate; C = Optional Rating of Evidence: I = One or more randomized trials with clinical outcomes and/or validated laboratory endpoints; II = One or more well-designed, nonrandomized trials or observational cohort studies with long-term clinical outcomes; III = Expert opinion |

| a It is important to assess and use individuals’ preferred terminology. Some may prefer using the term “chestfeeding” rather than “breastfeeding.” |

Risk of In Utero or Intrapartum HIV Transmission and Antiretroviral Management of Infants

All infants with in utero or intrapartum exposure to HIV should receive antiretroviral (ARV) drugs during the immediate neonatal period to reduce the risk of HIV transmission, with selection of the appropriate ARV regimen guided by the level of transmission risk. HIV transmission can occur in utero, intrapartum, or during breastfeeding.

This section addresses ARV management of infants with exposure to HIV-1 recommended by the Panel on the Treatment of HIV During Pregnancy and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission (Perinatal Panel) and the Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of Children Living With HIV (Pediatric Panel). Information about ARV management for infants born to people with HIV-2 infection is available in HIV-2 Infection and Pregnancy.

The viral load (HIV RNA level) of the birthing parent is the most important risk factor for in utero and intrapartum HIV transmission to the infant. Infants are at an increased risk for HIV acquisition when the birthing parent does not receive antiretroviral therapy (ART) during pregnancy and when antepartum treatment does not result in antepartum viral suppression, particularly in the 4 weeks prior to delivery, but even in the second half of pregnancy. Higher viral load correlates with higher risk of transmission. A spectrum of transmission risk depends on these and other factors, including mode of delivery and health status of the birthing parent. Although current assays can detect very low levels of HIV RNA, data from studies on transmission and viral load that were conducted prior to the availability of highly sensitive tests indicate that an HIV RNA level <50 copies/mL sufficiently predicts low risk of HIV transmission.1,2

Risk of HIV Transmission In Utero

The risk of in utero HIV transmission is believed to increase with gestational age, with the highest rate of in utero infection occurring in the third trimester. However, methodological challenges in assessing the timing of fetal infection limit the precision of risk estimates by gestational age. A definitive diagnosis of in utero infection during pregnancy would require invasive sampling, carrying risk that is not ethically or medically indicated. There are case reports of HIV being identified in fetal tissue as early as 8-, 15-, and 20-weeks’ gestation, but whether they represented established infection remains unclear.3-5 In a study of fetal thymuses in the second trimester, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing revealed that 2 of 100 samples had HIV-1.6 For this reason, the Panels have a 20 week–gestational age as a conservative gestational age threshold below which in utero transmission is unlikely to occur. A modeling study using profiles of viral culture positivity and seroconversion from a cohort of 95 French infants suggests that the vast majority of in utero HIV infection occurs in the third trimester.7 Another approach has been to examine how well ARVs initiated at different gestational ages prevent in utero transmission. Among 34 women in a U.K./Irish cohort who started ARVs during pregnancy, HIV transmission was more likely when ARVs were started later in pregnancy (median gestational age at initiation of 30.1 weeks, interquartile range [IQR] 27.4–32.6 weeks vs. 25.9 weeks, IQR 22.4–28.7 weeks, P < 0.001).8 Another model made estimates of relative time of in utero or intrapartum transmission based on timing of ARV initiation; they estimated 3% of transmissions occurred before 14 weeks’ gestation, 17% from 14 to 36 weeks, 50% from 36 weeks through onset of labor, and 30% from intrapartum exposure.9 In summary, in utero HIV transmission in the context of maternal viremia is considered rare in the first trimester, uncommon but possible in the second trimester, and most common in the third trimester.

Risk of HIV Transmission Intrapartum (During Labor and Delivery)

The highest risk of vertical HIV transmission is from exposure in the intrapartum period (i.e., during labor and delivery). Risk increases with the level of viremia in the birthing parent.2 Recommended interventions to reduce the risk of intrapartum transmission include ART for all birthing parents, intravenous zidovudine (ZDV) during labor and delivery, and scheduled cesarean delivery for birthing parents with detectable HIV-1 viral load >1,000 copies/mL (see Intrapartum Care for People With HIV).

Transmission Risk Assessment by HIV RNA Levels and Antenatal Time Period

Table 10 below summarizes in utero and intrapartum HIV transmission risk according to HIV RNA levels at three antenatal time periods for the purpose of selecting infant ARV prophylaxis. Because robust data are not available to define thresholds of risk across pregnancy, the Panels have defined time points balancing available evidence with implications for clinical management. Transmission risk categories inform ARV choice and management of prophylaxis and presumptive HIV therapy for infants with HIV exposure.

The assessment of transmission risk is generally but not exclusively dependent on HIV RNA levels during the antepartum period. The Perinatal Panel recommends assessing birthing parents’ HIV RNA levels at the initial antenatal visit with a review of prior levels, 2 to 4 weeks after initiating (or changing) ART, and monthly until RNA levels are undetectable. The birthing parent’s HIV RNA levels should also be assessed at least every 3 months during pregnancy and at approximately 36 weeks of gestation, or within 4 weeks of delivery (see Initial Evaluation and Continued Monitoring of HIV During Pregnancy). However, discussion around transmission risk may not align exactly with the recommended time frames, and clinicians must continue to utilize judgment to assess risk. For example, viremia could be presumed based on reports of poor adherence for several weeks, even without a documented test. Conversely, a missed HIV RNA test in a patient with years of virologic control may not merit concern. Incident HIV infection during pregnancy and lack of receipt of ART have been previously cited as risk factors for transmission; the current guidelines incorporate the risks of those scenarios within the framework of documented or presumed viremia.

| Antenatal Time Period | Transmission Risk | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV RNA at <20 Weeks’ Gestation | HIV RNA ≥20 Weeks’ Gestation to 4 Weeks Prior to Delivery | HIV RNA at ≤4 Weeks Prior to Delivery | In Utero | Intrapartum |

| N/Aa | N/Aa | ≥50 copies/mLb | High | High |

| N/Aa | ≥50 copies/mLb | <50 copies/mL | Low to moderate | Low |

| ≥50 copies/mLb | <50 copies/mL | <50 copies/mL | Low | Low |

| <50 copies/mL | <50 copies/mL | <50 copies/mL | Low | Low |

| a HIV RNA levels in this time period do not change the transmission risk categorization because transmission risk is determined by viremia later in gestation. b HIV RNA values of ≥50 copies/mL can be documented or presumed (e.g., early [acute or recent] HIV, new diagnosis of HIV, or known lapse in adherence). | ||||

Antiretroviral Management for Infants With In Utero or Intrapartum Exposure to HIV

Historically, the use of ARV drugs in the newborn period was referred to as ARV prophylaxis because it primarily focused on protection against newborn acquisition of HIV. More recently, clinicians have additionally sought to consider and optimize the management of newborns at elevated risk for HIV acquisition in utero and initiate three-drug ARV regimens as presumptive HIV therapy. In this section, the following terms will be used:

- ARV Prophylaxis: The administration of ARV drugs to a newborn without HIV infection to reduce the risk of HIV acquisition.

- Presumptive HIV Therapy: The administration of a three-drug ARV regimen to newborns at elevated risk of HIV acquisition. Presumptive HIV therapy is intended to be early treatment for a newborn who has already acquired HIV but doesn’t have documentation of infection; it also serves as enhanced ARV prophylaxis against HIV acquisition among infants at high risk but not yet infected.

- ART: The administration of a three-drug ARV regimen to infants and children with documented HIV infection (see Diagnosis of HIV Infection in Infants and Children and What to Start in the Pediatric Antiretroviral Guidelines).

The terms ARV prophylaxis and presumptive HIV therapy describe the potential roles of ARV drugs when the HIV status of an infant is unknown, and they often overlap in neonates at high risk. For example, a presumptive HIV therapy regimen also provides drug exposure that would serve as prophylaxis for a newborn. However, it is important to note that some two-drug and three-drug ARV regimens used historically were designed and studied as prophylaxis, including some that used doses of nevirapine (NVP) that target lower exposures than the doses used for treatment of HIV infection.

The Panels recommend initiating ARV prophylaxis or presumptive HIV therapy as soon as possible after birth, preferably within 6 hours. Although the maximum interval during which newborn ARV prophylaxis can be initiated and still be beneficial is unknown, most studies support providing ARV drugs as early as possible after delivery.10-15

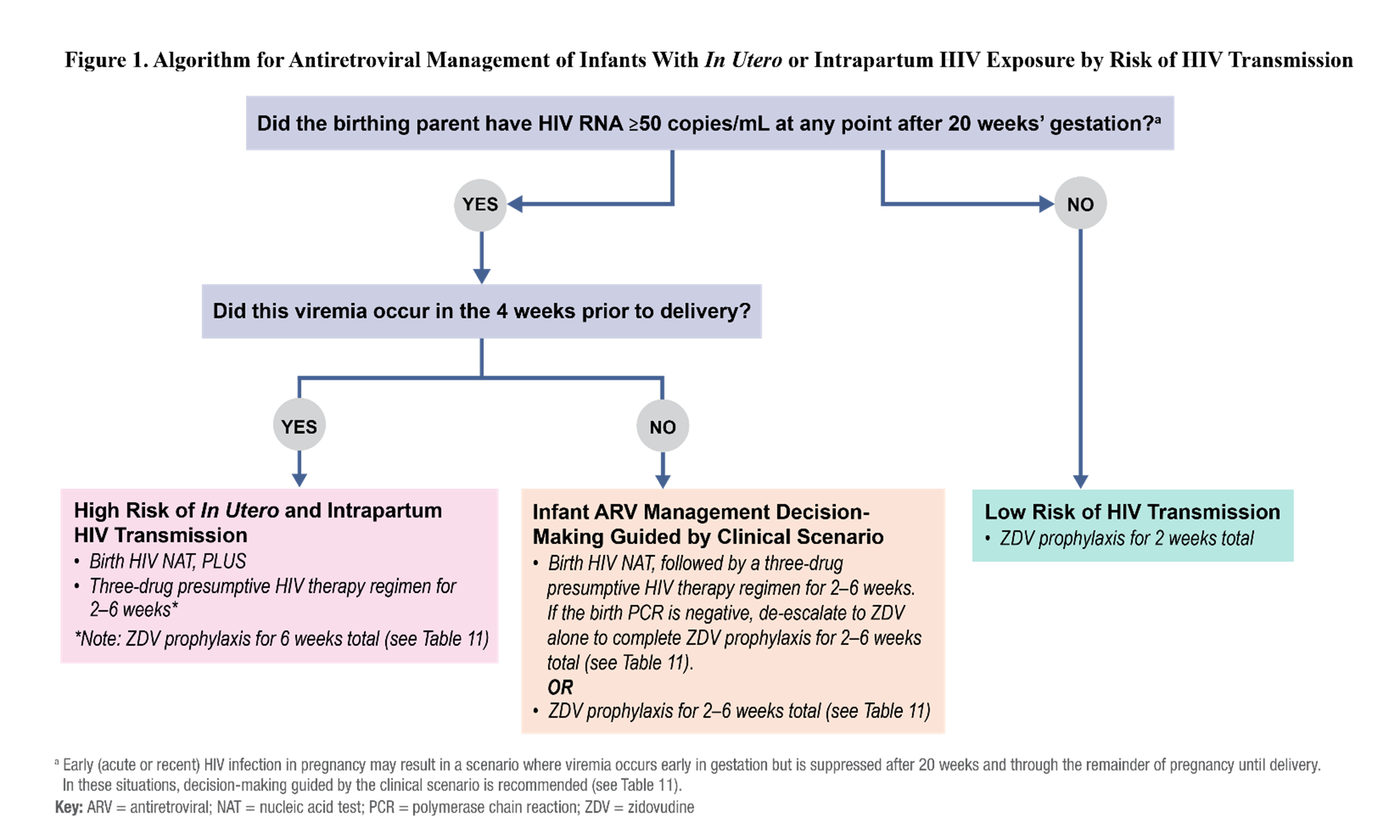

The guidance summarized in this section applies to infants of pregnant people with HIV unless otherwise noted. The algorithm in Figure 1 and Table 11 provide an overview of neonatal ARV management recommendations according to the risk of HIV transmission from in utero and intrapartum exposure based on HIV RNA levels at time points during pregnancy and other factors, such as receipt of and adherence to ART. Table 11.1 summarizes the recommended ARV dosing for prophylaxis or presumptive HIV therapy in newborns with in utero or intrapartum HIV exposure. Additional information about dose selection for newborns, including preterm infants (<37 weeks gestational age), can be found in Appendix A: Pediatric Antiretroviral Drug Information in the Pediatric Antiretroviral Guidelines.

The National Perinatal HIV Hotline (1-888-448-8765) is a federally funded service that provides free clinical consultation on difficult cases to providers who are caring for pregnant people with HIV and their newborns, and consultants can provide referrals to local or regional pediatric HIV specialists.

| Clinical Setting | Risk of Acquisition | Neonatal ARV Managementa,b | Rationale | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Utero | Intrapartum | |||

| High Risk of Acquisition | ||||

HIV RNA ≥50 copies/mL in the 4 weeks prior to delivery Viremia can be documented by lab or presumed by other clinical factors (e.g., new diagnosis, ART adherence problems, reports of having stopped ART prior to delivery). | High | High | Presumptive HIV therapy using a three-drug regimen of ZDV and 3TC plus either NVP (treatment dose) or RAL Duration is from birth for 2–6 weeks; consensus not reached by members of the Panel.c If the duration of a three-drug regimen is <6 weeks, and the birth NAT is negative, ZDV should be continued alone to complete a total of 6 weeks of prophylaxis. HIV NAT obtained before or immediately after starting presumptive therapy with three drugsd,e | Viremia in the 4 weeks immediately prior to delivery confers very high risk for in utero and intrapartum transmission. Plasma HIV RNA levels of 50–200 copies/mL could be expected to confer lower risk than those >200 copies/mL but could also be an indicator of poor adherence and raise concern for higher levels of viremia at other times. |

| Low Risk of Acquisition | ||||

HIV RNA <50 copies/mL from 20 weeks’ gestation through delivery Ideally documented by at least two consecutive tests at least four weeks apart with HIV RNA <50 copies/mL, but can be based on clinical judgment of providers. | Low | Low | ZDV for 2 weeks | Sustained virologic suppression from 20 weeks’ gestation is associated with extremely low risk of transmission in utero or intrapartum. Although in utero transmission events have been documented prior to 20 weeks, the extremely low frequency of these events does not merit the presumptive HIV therapy approach. |

| Other Clinical Scenarios | ||||

| HIV RNA ≥50 copies/mL at >20 weeks’ gestation, but HIV RNA <50 copies/mL in the 4 weeks prior to delivery | Low to Moderate | Low | HIV NAT at Birthd,e Two Options for ARV Management

| Viremia in the late second and third trimester elevates risk of in utero transmission (increasing risk with higher HIV RNA levels and longer duration of viremia). Option 1. Some Panel members believe that the potential benefit of early treatment for an infant who acquired the infection in utero merits a presumptive HIV therapy approach. Option 2. Other Panel members believe that the marginal potential benefit and anticipated low frequency of in utero infection do not merit the additional complexity of and potential toxicity of presumptive HIV therapy and favor ZDV prophylaxis only. All infants should receive a minimum of 2 weeks ZDV prophylaxis, but up to 6 weeks may be used when indicated based on risk assessment. |

| Early (acute or recent) HIV at any point during pregnancy | Moderate to High depending on the birthing parent’s HIV RNA levels and weeks’ gestation | High if HIV RNA ≥50 copies/mL in the last 4 weeks of pregnancy | HIV NAT at birthd,e Manage infant ARVs according to the level and timing of the birthing parent’s viremia as described in the rows above (just as for an infant of a birthing parent with established infection). | Early or recent HIV diagnosed at any time during pregnancy is a unique situation because very high HIV RNA levels place infants at high risk of HIV acquisition. For infants of people with known HIV infection, risk of transmission increases when viremia occurs later in pregnancy. Some Panel members would manage all cases with presumptive therapy, whereas others would only use it for viremia after 20 weeks’ gestation. |

Birthing parent with unconfirmed HIV status and who has at least one positive HIV test at delivery or postpartum or Birthing parent whose newborn has a positive HIV antibody test | High/Uncertain | High/Uncertain | HIV NAT at birthd,e Presumptive HIV therapy with a three-drug regimen as described above for newborns with a high risk of in utero or intrapartum HIV acquisition If supplemental testing confirms that the birthing parent does not have HIV, discontinue infant ARV drugs immediately. | Supplemental HIV testing of the birthing parent and/or NAT testing of the infant is required to determine the level of risk and need to continue infant presumptive HIV therapy or initiate ART.e |

| a Infant ARVs should be initiated in the first 6 hours after delivery, especially for infants with a high risk of acquisition. See Table 11.1 for ARV dosing. b See HIV-2 Infection and Pregnancy for ARV prophylaxis recommendations for infants born to a parent with HIV-2 mono-infection. If the birthing parent has HIV-2 infection or HIV-1 and HIV-2 coinfection, the infant ARV regimen should be based on the determination of low or high risk of HIV-1 transmission as described in the above table using ARVs that are active against HIV-2. Because HIV-2 is not susceptible to NVP, RAL should be used in presumptive HIV therapy regimens for infants at high risk of HIV acquisition with exposure to HIV-2 or to both HIV-1 and HIV-2. c The optimal duration of three-drug regimen in newborns who are at a high risk for HIV acquisition is unknown. Newborns who are at a high risk for HIV acquisition should receive the ZDV component for 6 weeks. The other two ARVs, (3TC and NVP) or (3TC and RAL), may be administered for 2 to 6 weeks; the recommended duration for treatment with three ARVs varies depending on infant HIV NAT results, the birthing parent’s viral load at the time of delivery, and the additional risk factors for HIV transmission. Consultation with an expert in pediatric HIV is recommended when selecting a therapy duration because this decision should be based on case-specific risk factors and interim infant HIV NAT results. d NAT test at birth should be obtained before or immediately after starting ARVs. See Diagnosis of HIV Infection in Infants and Children for additional information about HIV testing and NATs. e When a newborn HIV NAT is positive, infant ART should be initiated without waiting for the results of confirmatory HIV NAT testing, given the low likelihood of a false-positive HIV NAT (see When to Initiate Antiretroviral Treatment in Children with HIV Infection and What to Start in the Pediatric Antiretroviral Guidelines). However, the specimen for confirmatory HIV testing should be obtained prior to ART initiation. Note: Providers with questions about ARV management of infants should consult an expert in pediatric HIV infection or the National Perinatal HIV Hotline (1-888-448-8765). Key: 3TC = lamivudine; ART = antiretroviral therapy; ARV = antiretroviral; NAT = nucleic acid test; NVP = nevirapine; the Panels = the Panel on Treatment of HIV During Pregnancy and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission and the Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of Children Living With HIV; RAL = raltegravir; ZDV = zidovudine | ||||

Table 11.1. Drug Dosing Recommendations for Antiretroviral Prophylaxis and Presumptive HIV Therapy in Infants With In Utero or Intrapartum Exposure to HIVa

This table provides dosing for antiretroviral (ARV) prophylaxis and presumptive HIV therapy in infants with in utero or intrapartum exposure to HIV. Dosing for additional ARV prophylaxis during breastfeeding is provided in Table 12.1. Antiretroviral Prophylaxis Dosing for Infants Who Are Breastfed.

For infants with HIV infection, recommendations for initial ARV therapy regimens and ARV dosing are available in the Pediatric Antiretroviral Guidelines; see What to Start and Appendix A. Pediatric Antiretroviral Drug Information.

| ARV Drug | Drug Doses by Gestational Age at Birth | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

ZDV Note: For newborns who are unable to tolerate oral agents, the IV dose is 75% of the oral dose while maintaining the same dosing interval. | ≥35 Weeks Gestation at Birth Birth to Age ≤6 Weeks

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

≥30 Weeks to <35 Weeks of Gestation at Birth Birth to Age 2 Weeks

Age 2 Weeks to ≤6 Weeks

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

<30 Weeks Gestation at Birth Birth to Age 4 Weeks

Age 4 Weeks to ≤6 Weeks

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3TC | ≥32 Weeks’ Gestation at Birth Birth to Age <4 Weeks

Age ≥4 Weeks to ≤6 weeks

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

NVPb Note: These are NVP treatment doses for a presumptive HIV therapy regimen. NVP dosing for extended ARV prophylaxis during breastfeeding is provided in Table 12.1. Note: Do not use NVP if HIV-2 infection (or HIV-2 co-infection with HIV-1) is present or suspected; see HIV-2- Infection and Pregnancy. | ≥37 Weeks Gestation at Birth Birth to Age ≤6 Weeks

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

≥34 to <37 Weeks’ Gestation at Birth Birth to Age <1 Week

Age ≥1 Week to ≤6 Weeks

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

≥32 Weeks to <34 Weeks of Gestation at Birth Birth to Age <2 Weeks

Age ≥2 Weeks to <4 Weeks

Age ≥4 Weeks to ≤6 Weeks

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| RAL | ≥37 Weeks Gestation at Birth and Weighing ≥2 kgc Birth to Age 6 Weeks

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ABCd Note: The Panels do not recommend ABC as part of three-drug regimen for newborns with HIV exposure. However, in situations where ZDV is not available or the infant has ZDV-associated toxicity, ABC could be considered an alternative to ZDV. | ≥37 Weeks’ Gestation at Birth Birth to <1 Month

Age ≥1 Month to ≤6 Weeks

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

a The optimal duration of three-drug regimens for newborns at high risk of HIV acquisition is unknown; all infants should receive the ZDV component of the three-drug regimen for 6 weeks. The other two ARVs, (3TC and NVP) or (3TC and RAL), may be administered for 2 to 6 weeks; the recommended duration for these ARVs varies depending on infant HIV NAT results, viral load of the birthing parent at the time of delivery, and additional risk factors for HIV transmission. Consultation with an expert in pediatric HIV is recommended when selecting a therapy duration because this decision should be based on case-specific risk factors and interim infant HIV NAT results. d ABC is approved by the FDA for use in children aged ≥3 months when administered as part of an ARV regimen. ABC also has been reported to be safe in infants and children ≥1 month of age. More recently, an ABC dosing recommendation using PK simulation models has been endorsed by the WHO using weight-band dosing for full-term infants from birth to 1 month of age. See Abacavir in Appendix A: Pediatric Antiretroviral Drug Information in the Pediatric Antiretroviral Guidelines for additional information about the use of ABC between birth and 1 month of age. At this time, the Panels do not recommend ABC as part of a presumptive HIV therapy regimen. However, in situations where ZDV is not available or the infant has ZDV-associated toxicity, ABC could be considered an alternative to ZDV. This substitution should be considered in circumstances where increased risk of ZDV toxicity may exist, such as in infants with anemia or neutropenia. Because of ABC-associated hypersensitivity, negative testing for HLA-B*5701 allele should be confirmed prior to the administration of ABC. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Recommendations for Infant Antiretroviral Drugs in Specific Clinical Situations

In this section, Table 11. Antiretroviral Management for Infants With In Utero or Intrapartum Exposure to HIV, and Figure 1. Antiretroviral Management Algorithm for Infants With In Utero or Intrapartum HIV Exposure by Risk of Transmission, the Panels present available data and recommendations for ARV management of newborns born with in utero and intrapartum exposure to HIV.

Infants at High Risk of HIV Acquisition From In Utero or Intrapartum Exposure

The Panels recommend that all newborns at high risk for HIV acquisition from in utero and intrapartum exposure have an HIV nucleic acid test (NAT) at birth to determine in utero HIV infection status and receive presumptive HIV therapy (see Table 11 and Figure 1).14,16-21 HIV infection newly diagnosed during pregnancy is generally associated with high HIV RNA levels that would confer an elevated high risk of transmission to the infant, especially in the case of recent (early or acute) infection (see Table 11 and Early (Acute and Recent) HIV Infection).

Presumptive HIV Therapy

Early, effective treatment of HIV infection in infants restricts the viral reservoir size, reduces HIV genetic variability, and modifies the immune response.22-31 Because of these potential benefits of early ART the Panels recommend a three-drug presumptive HIV therapy regimen consisting of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (ZDV plus lamivudine [3TC]) plus either a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) (NVP at treatment dose, see Table 11.1) or an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI) (raltegravir [RAL]) for newborns at high risk of acquisition of HIV:

- ZDV plus 3TC plus NVP (at treatment dose, see Table 11.1) or

- ZDV plus 3TC plus RAL

If the birthing parent has HIV-2 infection or concomitant HIV-1 and HIV-2 infection, the RAL-containing regimen should be used for presumptive therapy because HIV-2 is not susceptible to NVP.

Although no clinical trials have compared the safety and efficacy of presumptive HIV therapy with single-drug or two-drug regimens, existing data suggest that presumptive HIV therapy in neonates has not been associated with serious adverse events (see Antiretroviral Drug Safety of Infant Prophylaxis below).

The pharmacokinetic (PK) and safety data of the three-drug regimens used for presumptive HIV therapy have provided reassuring evidence for its use in the neonatal period. Although the use of NVP to prevent HIV transmission has been found to be safe in neonates and newborns of low birthweight, these prophylaxis-dose regimens target trough drug levels that are at least tenfold lower than targeted therapeutic levels. However, studies of treatment doses of NVP and RAL have established safe doses that achieve targeted PK parameters.21,32-37

At this time, the Panels do not recommend abacavir (ABC) as part of a presumptive HIV therapy regimen. However, in situations where ZDV is not available or the infant has ZDV-associated toxicity, ABC could be considered an alternative to ZDV. This substitution should be considered in circumstances where an increased risk of ZDV toxicity may exist, such as in infants with anemia or neutropenia. Negative testing for HLA-B*5701 allele should be confirmed prior to the administration of ABC. New dosing recommendations for ABC in neonates based on the IMPAACT P1106 trial and two observational European and African cohorts are now available from the World Health Organization (WHO).38 ABC is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use in neonates and infants aged <3 months. However, 2 mg/kg per dose twice daily has been modeled using PK simulation and is endorsed by WHO using weight-band dosing for full-term infants from birth through 1 month of age. Limited observational data suggested safety of ABC when initiated in neonates <1 month of age (see Abacavir in the Pediatric Antiretroviral Guidelines).39

The optimal duration of a three-drug regimen in newborns at high risk of HIV acquisition is unknown. Consulting an expert in pediatric HIV is recommended when selecting a therapy duration based on case-specific risk factors and interim HIV NAT results. HIV NAT diagnostic testing at birth (prior to or immediately after starting ARVs) is recommended for infants at high risk for HIV acquisition. A positive birth NAT test indicates in utero HIV infection. Panel members varied in their recommendations for the duration of presumptive HIV therapy. Some Panel members would opt to discontinue additional medications and complete 6 weeks ZDV prophylaxis alone if infant birth NAT results are negative, whereas other Panel members would continue presumptive HIV therapy for 2 to 6 weeks, depending on the risk of HIV transmission. Panel members agreed that ZDV should be continued for 6 weeks in all scenarios, regardless of the duration of the other two drugs. If the birth NAT is positive, the infant should receive an ART regimen recommended for the treatment of HIV infection (see What to Start: Antiretroviral Treatment Regimens Recommended for Initial Therapy in Infants and Children With HIV and Appendix A: Pediatric Antiretroviral Drug Information in the Pediatric Antiretroviral Guidelines).

Newborns at Low Risk of HIV Acquisition from In Utero or Intrapartum Exposure

An infant born to a parent with HIV RNA levels <50 copies/mL and no HIV RNA levels ≥50 copies/mL after 20 weeks’ gestation is considered to have low risk of HIV acquisition and should receive prophylaxis with ZDV alone for 2 weeks.

The risk of HIV acquisition in newborns born to people who received ART during pregnancy and labor and who had undetectable viral load near or at the time of delivery is <1%.2 In the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group (PACTG) 076 study, ZDV alone reduced the incidence of HIV transmission by 66%, and ZDV is recommended as prophylaxis for neonates when the birthing parent received ART that resulted in consistent viral suppression during pregnancy.40 Other studies have also compared NVP to ZDV infant prophylaxis.41,42 The ANRS French Perinatal Cohort observed that NVP infant prophylaxis was associated with less anemia than ZDV infant prophylaxis. The optimal minimum duration of neonatal ZDV prophylaxis has not been established in clinical trials. A 6-week ZDV regimen was studied in newborns in PACTG 076.43 However, evidence supporting a reduced duration of ZDV prophylaxis in infants born to people who were suppressed virologically during pregnancy and at the time of delivery is mounting.44-46

No studies directly compare the efficacy of a 2-week versus 4-week duration of infant ZDV prophylaxis. However, high-income countries have some experience with a 2-week duration of infant prophylaxis. The United States, as well as the United Kingdom and other European countries, recommends a 2-week neonatal ZDV prophylaxis regimen when the risk of HIV acquisition from exposure is low and/or very low, with varying criteria across countries47,48 Compared with the 6-week ZDV regimen, a 2 to 4 week ZDV regimen has been reported to allow earlier recovery from anemia in otherwise healthy newborns.49,50 In a cohort of 87 Swiss infants born to women with HIV RNA levels <50 copies/mL in the last trimester who did not receive ARV prophylaxis, in accordance with Swiss ARV guidance at that time, none acquired HIV infection.51

Other Clinical Scenarios

An infant born to a parent who had HIV RNA levels ≥50 copies/mL after 20 weeks of gestation but had HIV RNA levels <50 copies/mL for the 4 weeks prior to delivery is considered to have low-to-moderate risk for in utero and low risk for intrapartum acquisition of HIV (see Table 10). This assessment takes into consideration that low-level viremia could reflect intermittent adherence between laboratory tests. Low-level viremia (e.g., ≥50 copies/mL to 200 copies/mL) is not expected to confer a high risk of in utero transmission of HIV but has been associated with elevated risk of subsequent virologic failure.52,53 The Panels did not reach consensus on infant ARV management (see Table 11) for this clinical scenario and consider factors such as the magnitude and duration of elevated HIV RNA levels,2 the birthing parent’s adherence to ART, and parental input in decision-making.

Some Panel members recommend that these infants receive presumptive HIV therapy until the results of birth HIV NAT are available. If the birth HIV NAT is negative, excluding in utero HIV acquisition, the Panels recommend de-escalation of presumptive HIV therapy to ZDV prophylaxis to complete ZDV for a total of 6 weeks. This provides a balanced risk/benefit approach to quickly identifying in utero HIV acquisition, limiting exposure to presumptive HIV therapy in the event HIV transmission has not occurred in utero, and promptly administering very early presumptive therapy in the event of in utero infection. Very early ART has been shown to provide durable virologic suppression and reduce early viral reservoirs enabling HIV remission in some children with in utero HIV acquisition.31,54 See When to Initiate Antiretroviral Therapy in Children With HIV Infection. However, other Panel members argue that the data supporting the potential benefit of early ART has not been demonstrated for this specific scenario, would likely apply to a small number of infants, and carries risk of avoidable toxicity to infants without in utero infection; for these reasons, they recommend 2 to 6 weeks of ZDV prophylaxis. Providers must decide which rationale aligns with their own assessment and should consider involving parents in the decision.

When a birthing parent is diagnosed with early (acute or recent) HIV during pregnancy, infant ARVs should be managed according to the gestational timing of the parent’s viremia (see Table 11). Because HIV RNA levels are generally very high in these situations, some Panel members would manage all infants with a three-drug ARV regimen even if the birthing parent had undetectable viral load after 20 weeks. Other Panel members would base decisions about infant ARVs on the timing of viremia.

Infants of birthing parents who have a positive HIV test at delivery or postpartum and infants who have a positive HIV antibody test after birth should receive a three-drug regimen as described above for infants at high risk of HIV acquisition. If supplemental testing confirms that the birthing parent does not have HIV, infant ARV drugs should be discontinued immediately.

Newborns Born to Birthing Parents With Antiretroviral Drug-Resistant Virus

The optimal approach to selecting an ARV regimen for newborns born to birthing parents with ARV drug-resistant virus is unknown. Some studies have suggested that ARV drug-resistant virus may have decreased replicative capacity (reduced viral fitness) and transmissibility.55 The transmission of drug-resistant virus to infants does occur.56-62 Whether resistant virus in the birthing parent increases the risk of vertical HIV acquisition by the infant remains unclear. A secondary analysis of data from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development–HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) 040/PACTG 1043 did not find that the presence of drug-resistance mutations in birthing parents who had not received ARV drugs before the start of the study increased the risk of in utero or peripartum transmission (adjusted odds ratio 0.8; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.4–1.5).61 However, a case-control study found that resistance to NNRTIs in the breastfeeding parent was an independent risk factor for the vertical transmission of HIV during breastfeeding in the PROMISE trial.63

Although no trials have compared the efficacy of neonatal prophylaxis regimens customized to address drug resistance in the birthing parent, the Panels recommend considering drug resistance in the parent when selecting the three-drug regimen for presumptive HIV therapy. For example, an infant at high risk of infection born to a pregnant person with HIV with NNRTI resistance could potentially benefit from a three-drug regimen based on RAL rather than NVP. However, other factors must also be considered, such as gestational age (limits the number of agents with available dosing) and feasibility for the parent to administer the regimen (e.g., the preparation of RAL is more difficult than NVP).

Maraviroc (MVC) has been approved recently for infants ≥2 kg and may provide an additional ARV option for newborns of birthing parents carrying multidrug-resistant HIV-1 that remains CCR5-tropic.64 However, the lack of data about MVC as prophylaxis or treatment in infants and the risk of drug interactions will limit its role for routine use in neonates.

For assistance in selecting a three-drug ARV regimen for newborns born to birthing parents with known or suspected drug resistance, consultation with a pediatric HIV specialist or the National Perinatal HIV hotline (1-888-448-8765) is recommended.

Antiretroviral Prophylaxis for Infants Who are Being Breastfed by a Parent With HIV

Individuals with HIV should be counseled about infant feeding options (e.g., formula feeding, banked donor human milk, breastfeeding) throughout pregnancy. The conversation should include decision-making about the risk and potential benefits of ARV prophylaxis. Recommendations and dosing for infant ARV prophylaxis during breastfeeding are summarized in Table 12 and Table 12.1. In general, infant ARV prophylaxis during breastfeeding should begin after initial ZDV prophylaxis is completed. However, some experts recommend initiating ARV prophylaxis with NVP or 3TC in place of ZDV from birth for simplicity. The duration of extended infant ARV prophylaxis can also vary based on provider and parent preference. The most conservative course is to continue prophylaxis until 6 weeks after the last exposure to breast milk. However, a parent may exhibit long-standing virologic suppression during breastfeeding, and with their provider’s guidance, may decide to stop prophylaxis while continuing to breastfeed. The Panels recommend patient-centered, evidence-based counseling to support shared decision-making about infant feeding. See Infant Feeding for Individuals With HIV in the United States for more information on counseling, management, and monitoring.

Antiretroviral Prophylaxis for Breastfeeding Infants of Parents With Sustained Virologic Suppression (HIV RNA <50 Copies/mL)

The Panels could not reach consensus on recommendations regarding the use of extended infant ARV prophylaxis during breastfeeding. For infants considered to be at low risk, Panel members agreed on the provision of 2 weeks of ZDV to infants for standard prophylaxis for HIV exposure, but some Panel members prefer to extend the duration of ZDV prophylaxis to 4 to 6 weeks when the infant is being breastfed. For the period after initial postnatal prophylaxis, some Panel members recommend no additional prophylaxis when virologic suppression is maintained throughout breastfeeding, but other Panel members recommend extended ARV prophylaxis with NVP or 3TC during breastfeeding. Both NVP and 3TC have been used effectively for extended prophylaxis during breastfeeding.65,66 3TC has been studied through 12 months of age and requires twice-daily administration.66 NVP has been studied through 18 months of age and is given once daily.65 Concerns related to the use of NVP include impaired efficacy in the context of NNRTI resistance in the breastfeeding parent and the development of NNRTI resistance if an infant acquires HIV while receiving NVP during breastfeeding (see Newborns Born to Birthing Parents With Antiretroviral Drug-Resistant Virus above).

When extended prophylaxis is used, most experts recommend transitioning to NVP or lamivudine 3TC after completion of the initial ZDV prophylaxis. However, NVP can be given from birth, replacing ZDV and providing both initial postnatal prophylaxis and extended prophylaxis during breastfeeding. ZDV should not be used for a period of more than 6 weeks.

Given the lack of consensus by the Panels for a recommendation about extended ARV prophylaxis during breastfeeding, the Panels advise providers to involve the parent(s) in open discussion and shared decision-making, weighing values about risk tolerance (for transmission and toxicity) and other issues related to infant prophylaxis (e.g., prematurity). For additional information, see Safety of Antiretroviral Drugs Used for Infant Prophylaxis below.

Most data to guide decisions infant ARV prophylaxis during breastfeeding are from studies in sub-Saharan Africa, where breastfeeding is recommended for all birthing parents with HIV infection and standard practice for prophylaxis also differs. The WHO recommends six weeks of NVP for all infants who are breastfed by a parent who is receiving ART in resource-limited countries.67 In the PROMISE study, among 1,219 infants of mothers on ART, there were seven HIV transmissions reported. Among these, five mothers had documented detectable viral loads immediately prior to the first report of the infant’s positive HIV NAT; the remaining two mothers had elevated viral loads in subsequent testing.68 Note that these two infants had their first detectable HIV NAT at weeks 13 and 38 of life, beyond 6 weeks of age where infant NVP was administered according to WHO guidelines.

In the Breastfeeding, Antiretrovirals, and Nutrition study, a sub-study of 31 infants with HIV and 232 infants who were uninfected and their mothers69 demonstrated that there were no HIV transmissions when the mother consistently maintained a viral load less than 100 copies/mL. Bispo et al. have reported a meta-analysis of 11 studies of breastfeeding mothers with HIV who started ART before or during pregnancy and continued until at least 6 months postnatally.70 This meta-analysis was limited by the heterogeneity in studies but reported an overall postnatal HIV transmission rate of 1.08% (95% CI, 0.32–1.85) at 6 months in infants who tested HIV negative at 4 to 6 weeks of age. In a post-hoc analysis of the HPTN 046 study, which showed <1% risk of postnatal HIV transmission in both the extended NVP and placebo arms, the addition of infant prophylaxis did not further reduce breastfeeding transmission in mothers who were receiving ART.71

See ARV Prophylaxis for Infants When There Is a Concern About Risk of Future Viremia During Breastfeeding, below, for additional data supporting the efficacy of NVP and 3TC as prophylaxis during breastfeeding.

Taken together, existing data support the efficacy of ART in the breastfeeding parent with documented sustained viral suppression to prevent postnatal transmission of HIV, suggesting that the recommended management of 2 weeks of ZDV prophylaxis for infants at low risk of in utero or intrapartum exposure is appropriate for breastfed infants when the breastfeeding parent has had sustained HIV RNA levels of <50 copies/mL. This approach is currently recommended by the British HIV Association (BHIVA).47

Table 12. Antiretroviral Management of Infants With Exposure to HIV During Breastfeeding

HIV RNA levels of the parent should be monitored periodically during breastfeeding because the status of viral suppression can change over time (see Infant Feeding for Individuals With HIV in the United States). Decisions about infant antiretroviral (ARV) management during breastfeeding should be based on clinical assessment and incorporate shared decision-making when indicated.

Providers with questions about ARV management of infants should consult an expert in pediatric HIV infection or the National Perinatal HIV Hotline (1-888-448-8765).

| Level of Transmission Risk During Breastfeeding by HIV RNA Levels in Breastfeeding Parent | Description | Infant ARV Management During Breastfeedinga |

|---|---|---|

| Sustained Viral Suppression (HIV RNA <50 copies/mL) | When the breastfeeding parent has had sustained virologic suppression during pregnancy (at a minimum during the third trimester, documented by at least two HIV RNA measurements below the limits of detection at least 1 month apart) and breastfeeding and there are no concerns about adherence |

|

| Current HIV RNA Levels <50 copies/mL But Concerns About Future Risk | When the breastfeeding parent has virologic suppression during pregnancy but there is concern about future risk (e.g., ART adherence or loss of virologic suppression for other reasons) during breastfeeding |

|

| New Viremia During Breastfeeding (HIV RNA ≥200 copies/mL) | When the breastfeeding parent develops viremia with HIV RNA ≥200 copies/mL or presumed viremia (e.g., nonadherence, interrupted access to ARVs) |

|

| New Viremia During Breastfeeding (HIV RNA <200 copies/mL) | The Panels did not reach consensus about neonatal management when the breastfeeding parent develops viremia that is quantifiable but <200 copies/mL. |

|

| Parent With a New Diagnosis of HIV When Breastfeeding | Parent is newly diagnosed with HIV while they are breastfeeding their infant |

|

| a An HIV NAT at birth is recommended for all breastfeeding infants. A NAT should be obtained before or immediately after starting ARVs. See Diagnosis of HIV Infection in Infants and Children for additional information about infant NATs during breastfeeding and follow-up testing after viremia in the breastfeeding parent. b DTG, a second-generation integrase strand transfer inhibitor with a higher barrier to resistance than RAL, can be used in infants aged ≥4 weeks and weighing ≥3 kg. Note: Given limited data, decisions about infant ARV prophylaxis during breastfeeding should be based on shared decision-making with the infant’s parents. Key: 3TC = lamivudine; ART = antiretroviral therapy; ARV = antiretroviral; DTG = dolutegravir; NAT = nucleic acid test; NVP = nevirapine; the Panels = Panel on Treatment of HIV During Pregnancy and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission and Panel on Antiretroviral Therapy and Medical Management of Children Living With HIV; RAL = raltegravir; ZDV = zidovudine | ||

| ARV Prophylaxis for Infants When the Breastfeeding Parent has Sustained Viral Suppression | |

|---|---|

| Recommended Regimen | Recommended Duration and Dosing |

| ZDV | ZDV administered for 2 weeks after birth (see Table 11 for dosing) |

| Options for Extended Postnatal Prophylaxisa | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended Regimen | Recommended Duration and Dosing | ||||||||||

| ZDV | ZDV administration continued for 4–6 weeks after birth (See Table 11.1 for dosing; note that ZDV is not recommended for prophylaxis beyond this initial postnatal period.) | ||||||||||

| NVPb,c | NVP administered starting at birth or after completion of initial prophylaxis ZDV, through 6 weeks after cessation of breastfeeding

| ||||||||||

| 3TC | 3TC administered starting after completion of initial prophylaxis ZDV, through 6 weeks after cessation of breastfeeding Age 2 Weeks to <4 Weeks

Age ≥4 Weeks to 12 months

| ||||||||||

| Recommended Infant ARV Management When a Breastfeeding Parent Develops Viremia or Is Diagnosed With HIV During Breastfeedinga | |

|---|---|

| Presumptive HIV Therapy Regimens | Recommended Duration and Dosing |

| ZDV plus 3TC plus DTGe | Three-drug presumptive HIV therapy regimen. ZDV and 3TC plus NVP or RAL should be used in place of DTG for infants aged <4 weeks and/or weighing <3 kg.e,f See Table 11.1 for dosing of ZDV and 3TC in infants aged <6 weeks. Refer to drug sections in Appendix A: Pediatric Antiretroviral Drug Information for appropriate age-based dosing of DTG and for dosing of ZDV, 3TC, NVP, or RAL in infants aged >6 weeks. Presumptive HIV therapy is recommended for a duration of 2–6 weeks (see Table 12). |

| a Consultation and referrals to local or regional Pediatric HIV specialists are available through the National Perinatal HIV Hotline (1-888-448-8765). b NVP dosing is adapted from the Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Prevention, Testing, Treatment, Service Delivery and Monitoring: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach. For infants at low risk of transmission, these doses can be given from birth. (Simplified Age-Based Dosing for Newborns ≥32 Weeks’ Gestation Receiving Extended NVP Prophylaxis During Breastfeeding in the World Health Organization’s Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Prevention, Testing, Treatment, Service Delivery and Monitoring: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach, July 2021) c 3TC should be used as extended ARV prophylaxis during breastfeeding when there is evidence or concern for NVP resistant virus (including HIV-2 infection or HIV-1/HIV-2 co-infection) in breastfeeding parent or when an infant cannot tolerate NVP. Dosing recommendations for 3TC are included in the table. d Dosing for extended 3TC prophylaxis during breastfeeding, based on established 3TC dosing for treatment and weight-band dosing used in PROMISE-EPI Source: Mennecier A, Kankasa C, et al. Optimised prevention of postnatal HIV transmission in Zambia and Burkina Faso (PROMISE-EPI): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2024;403(10434):1362-1371. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38484756. e DTG, a second-generation integrase strand transfer inhibitor with a higher barrier to resistance than RAL, is preferred in infants aged ≥4 weeks and weighing ≥3 kg. f When a parent is diagnosed with HIV infection while breastfeeding, a three-drug presumptive HIV therapy regimen is recommended for the infant, with a duration of 2–6 weeks (see Table 12.1). The same regimen is recommended for infants at high risk of HIV acquisition after in utero or intrapartum exposure (see Table 11 and Table 11.1). No trials have evaluated the use of multidrug regimens to prevent transmission after cessation of breastfeeding by a parent with early (acute or recent) HIV infection. Some Panel members recommend presumptive HIV therapy until the infant’s HIV status can be determined. If the infant’s initial HIV NAT is negative, the optimal duration of presumptive HIV therapy is unknown. A 28-day course may be reasonable based on current recommendations for nonoccupational HIV exposure. Key: 3TC = lamivudine; ARV = antiretroviral; NVP = nevirapine; RAL = raltegravir; ZDV = zidovudine | |

Antiretroviral Prophylaxis for Infants When There Is Concern About the Risk of Future Viremia During Breastfeeding

For some parents interested in breastfeeding who meet the criteria for the lowest anticipated risk of breast milk transmission, with current and recent HIV RNA levels of <50 copies/mL, there may be concern about future adherence in the postpartum period or factors that may impact virologic suppression (e.g., postpartum depression, interrupted access to ARVs).72 Lapses in adherence in the postpartum period are common, with increased risk among women of younger age and more recent ART initiation.73 Providers may consider additional adherence history and postpartum adherence challenges following prior pregnancies when making recommendations about infant prophylaxis during breastfeeding. There may be anticipated changes in social structure, such as moving to a new home, in the postpartum period that may generate new challenges to adherence. It is also important for providers to elicit parents’ concerns, regardless of the provider’s assessment. If there are concerns about ARV adherence during breastfeeding, the Panels recommend extended infant ARV prophylaxis during breastfeeding with either NVP or 3TC and the addition of adherence support for the breastfeeding parent (see Table 12 and Table 12.1).

Data suggest that infant prophylaxis can be very effective in preventing breast milk transmission in the context of maternal viremia. In the PROMISE trial, only 7 of the 1,211 (0.58%) analyzed infants in the infant NVP prophylaxis arm acquired HIV infection.68 A randomized controlled trial in Burkina Faso and Zambia found that initiation of same day infant 3TC prophylaxis in women with a viral load of >1,000 copies/mL during breastfeeding resulted in a reduction in postnatal HIV transmission compared to local standard of care.66 Although findings did not reach statistical significance because the study was underpowered, the findings suggest that early infant diagnosis, in conjunction with on-demand HIV RNA testing in the breastfeeding parent and extended infant prophylaxis, could be a valuable approach in eliminating postnatal HIV transmission risk. A pooled analysis of these trials reported that mothers with a viral load of 40 to 1,000 copies/mL in the initial 6 to 8 weeks postpartum were at high risk for having a viral load >1,000 copies/mL at 6 or 12 months postpartum.74 Given the efficacy demonstrated in the trials, the Panels believe that extended ARV prophylaxis should be considered for breastfeeding infants when there is concern about future risk of HIV exposure during episodes of viremia in breastfeeding parents.

Antiretroviral Prophylaxis for Infants of Parents Who Develop Detectable HIV RNA During Breastfeeding

Parents should receive counseling and be involved in decision-making about infant ARV prophylaxis and management of infant feeding. In situations where there is increased risk of postnatal transmission due to the development/occurrence of viremia during breastfeeding, the Panels advise initiation of additional infant ARV prophylaxis to prevent breastfeeding-associated HIV transmission. When a parent with HIV develops detectable HIV RNA levels during breastfeeding, the infant should be tested for HIV infection (using a NAT) prior to or immediately after initiating ARVs, as well as at specified time points after cessation of breastfeeding and completion of presumptive HIV therapy (see Diagnosis of HIV Infection in Infants and Children and Table 13. Recommended Virologic Testing Schedule for Infants With Perinatal and Breastfeeding Exposure to HIV). If infant HIV testing returns a positive HIV NAT result, see Infants with HIV Infection below and What to Start in the Pediatric Antiretroviral Guidelines).

When the parent develops new viremia, the Panels recommend that breastfeeding be stopped temporarily or discontinued and replacement feeding initiated (see Situations to Consider Modifying or Stopping Breastfeeding in Infant Feeding for Individuals with HIV in the United States). Most experts recommend permanent discontinuation of breastfeeding when HIV RNA is ≥200 copies/mL. This guidance is more directive than counseling for individuals on suppressive ART. In situations where viremia is lower and an addressable cause has been identified, the added risk of short term continued breastfeeding would be less.

Breastfeeding Parent Who Develops New Viremia With HIV RNA ≥200 Copies/mL

In cases where the breastfeeding parent develops new viremia with an HIV RNA level ≥200 copies/mL, the Panels recommend immediate initiation of infant presumptive HIV therapy using a three-drug regimen of ZDV plus 3TC plus DTG (NVP or RAL in place of DTG, if infant age < 4 weeks) (see Table 12 and Table 12.1 above). The drugs should be administered together for 2 to 6 weeks, with duration based on timing of results of infant NAT. As for management of high risk around the time of birth, if 3TC plus (DTG or NVP or RAL) are discontinued, ZDV should be continued alone to complete a total of 6 weeks prophylaxis.

As noted above, in cases where the breastfeeding parent develops new viremia with an HIV RNA level ≥200 copies/mL, the Panels recommend permanent cessation of breastfeeding. However, some parents may continue to breastfeed in which case longer durations of ARVs for infants may be indicated. Discussion with parents and consultation with the National Perinatal HIV Hotline (1-888-448-8765) or consultation with another expert is suggested.

Breastfeeding Parent Who Develops New Viremia With HIV RNA <200 Copies/mL

In cases where the breastfeeding parent develops new viremia that is quantifiable but with HIV RNA <200 copies/mL, some Panel members recommend initiation of presumptive HIV therapy for the infant, other Panel members recommend initiation of single-drug ARV prophylaxis (with NVP or 3TC), and other Panel members recommend infant ARV management based on repeat HIV RNA testing of the breastfeeding parent. The rationale for the cutoff of 200 copies/mL is that low-level viremia <200 copies/mL has been shown to predict future virologic failure with HIV RNA >200 copies/mL.75 The Panels did not reach consensus about infant ARV prophylaxis or presumptive HIV therapy in this situation (see Table 12). Discussion with parents and consultation with the National Perinatal HIV Hotline (1-888-448-8765) or consultation with another expert is suggested.

Special Situations in Breastfeeding Infants

Initiation or Continuation of Breastfeeding By a Parent With Viremia

The Panels strongly advise against initiating or continuing breastfeeding infants at high risk of HIV acquisition from in utero, intrapartum, and/or postnatal exposure. Replacement feeding with formula or banked pasteurized donor human milk is recommended given the high risk of postnatal HIV transmission associated with viremia during breastfeeding (see Infant Feeding for Individuals With HIV in the United States). Discussion with parents and consultation with the National Perinatal HIV Hotline (1-888-448-8765) or consultation with another expert is recommended.

Infants of Parents Who Receive an HIV Diagnosis While Breastfeeding

People with suspected HIV (e.g., a positive initial screening test) should discontinue breastfeeding immediately, until HIV is ruled out. Pumping and temporarily discarding or freezing breast milk can be recommended to breastfeeding parents who are suspected of having HIV but whose HIV serostatus is not yet confirmed and who want to continue to breastfeed. If HIV is ruled out, breastfeeding can resume. Given the high risk of HIV transmission when HIV is acquired or diagnosed during breastfeeding, the Panels advise against breastfeeding and recommend replacement feeding with formula or banked pasteurized donor human milk if HIV infection is confirmed in the breastfeeding parent.76 See New HIV Diagnosis of a Breastfeeding Parent in Diagnosis of HIV Infection in Infants and Children for guidance about infant testing.

Infants breastfed by a parent who just learned of their own HIV diagnosis during breastfeeding are considered to be at high risk of HIV acquisition and treated accordingly with a three-drug presumptive HIV therapy regimen for 2 to 6 weeks (see Table 12 and Table 12.1). No trials have evaluated the use of multidrug regimens to prevent transmission after cessation of breastfeeding by a parent with early (acute or recent) HIV infection. Given the higher risk of postnatal transmission from a person with early (acute or recent) HIV infection who is breastfeeding, an alternative approach favored by some Panel members is to offer presumptive HIV therapy until the infant’s HIV status can be determined. If the infant’s initial HIV NAT is negative, the optimal duration of presumptive HIV therapy is unknown. A 28-day course may be reasonable based on current recommendations for nonoccupational HIV exposure. The National Perinatal HIV Hotline (1‑888‑448-8765) can provide referrals to local or regional pediatric HIV specialists.

Safety of Antiretroviral Drugs Used for Infant Prophylaxis

This section is intended to provide the information needed for clinical management and counseling parents on decision-making around infant prophylaxis. When used alone for prophylaxis in low-risk scenarios during the neonatal period and breastfeeding, ARVs appear highly safe. The most prominent toxicity in the neonatal period is anemia from ZDV given alone or in combination regimens; anemia occurs after 2–4 weeks but recovers with the cessation of treatment to levels similar to controls (see Initial Postnatal Management of the Neonate Exposed to HIV. During the breastfeeding period, 3TC has been shown to be safe through at least 41 weeks. NVP has been shown to be safe for infants from birth through 18 months of life; one trial identified cases with concerns of a hypersensitivity reaction, but larger subsequent trials did not report hypersensitivity reactions. Three-drug combinations appear safe within the durations currently recommended (i.e., 2–6 weeks).

Based on existing safety data, longitudinal laboratory monitoring for adverse events is not needed in otherwise healthy infants receiving currently recommended ARVs used for prophylaxis in the first 6 weeks of life. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends periodic monitoring of hematologic and liver toxicity in breastfeeding infants receiving ARV prophylaxis beyond this period and for extended durations.77

Zidovudine

ZDV was the first agent studied for prophylaxis against HIV transmission to infants and remains the standard of care for prophylaxis in low-risk situations. The major side effect from short-term (6 weeks or less) use of ZDV appears to be transient anemia.

- In the landmark PACTG 076 trial, 415 infants were randomized and received ZDV or placebo; hemoglobin levels in the ZDV arm were lower at the end of the 6-week treatment course but recovered and were equivalent between arms by 12 weeks.43 No other toxicities were significantly different between arms, and no new toxicities were identified through 18 months of follow up.78

- Subsequent trials of 6-week regimens of ZDV alone did not identify other significant toxicities.20

- A 4-week ZDV regimen, compared with the 6-week ZDV regimen, has been reported to result in earlier recovery from anemia in infants who are HIV-exposed but otherwise healthy.49 Severe cases of anemia can be treated with erythropoietin79; substitution of ZDV with 3TC and/or NVP41 can also be considered.

Lamivudine

3TC has been extensively studied in combination with ZDV, but data primarily from two trials support the safety of 3TC used alone as prophylaxis during breastfeeding through at least 41 weeks of life.

- The Mitra Study was an open-label single-arm prospective cohort trial in which 398 infants were treated with ZDV + 3TC from birth to 1 week of age, and then with 3TC alone for the duration of breastfeeding (maximum of 6 months) plus 2 weeks after stopping breastfeeding.80 No serious adverse events were attributed to the study drug.

- In ANRS 12174, 1,273 infants were randomized at 7 days to receive either lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r) or 3TC through the completion of breastfeeding (median duration 41 weeks)81; there were no differences in adverse events rates between the arms.

- In ANRS 12397 PROMISE-EPI, in infants breastfed by people with HIV who were viremic during pregnancy, 3TC was initiated as prophylaxis at 6 weeks and 6 months, and continued through 12 months of age; the initial report noted no safety concerns, but the full results have not yet been published.82,83

Nevirapine

Several trials support the safety of once-daily NVP in the first 6 weeks of life and through breastfeeding. Although reactions concerning hypersensitivity were reported in the Breastfeeding, Antiretrovirals, and Nutrition (BAN) trial, no cases have been identified in subsequent large trials or from clinical programs. Strong data also support the safety of twice-daily NVP used in a three-drug presumptive HIV therapy regimen.

- In the SWEN trial, infants were randomized to either single dose (n = 1,047) or 6-week courses (n = 977) of once-daily NVP; adverse events were common overall (~40%) but without significant differences by arm.81

- In the BAN trial, 2,369 mother-infant dyads were randomized to infant prophylaxis with once-daily NVP, maternal ARV treatment, or enhanced control until the cessation of breastfeeding but no longer than 28 weeks.84 A hypersensitivity reaction (rash, with eosinophilia in 10 infants, with or without fever) developed in 16 (1.9%) infants within 4 weeks after the initiation of NVP therapy; reactions resolved after NVP was replaced with 3TC. Hypersensitivity was the only adverse event significantly different between arms.

- In HPTN 046, 1,519 breastfeeding infants were randomized to 6 months of once-daily NVP or placebo (after 6 weeks of NVP from birth); no differences in adverse event rates were noted by arm through 12 months of follow up.81

- In the PEPI-Malawi trial, 3,016 infants were randomized to receive NVP with 1 week of ZDV (control), once daily NVP extended through 14 weeks, or NVP + ZDV extended through 14 weeks.85 Among the three arms, no significant differences were seen in serious adverse event rates overall, nor among adverse events deemed probably associated with study drugs. However, the extended NVP + ZDV arm had significantly more serious adverse events deemed possibly related to NVP or ZDV, the most common of which was neutropenia.

- In IMPAACT 1077BF, the breastfeeding component of the PROMISE trial, 2,431 mother-infant dyads were randomized to either maternal ART or infant NVP prophylaxis (once daily) continued until 18 months after delivery or breastfeeding cessation65; the median duration of breastfeeding was 16 months in both arms. No differences were seen between study arms in Grade 3 or 4 adverse event rates or liver or skin toxicity. Of the 1,204 infants in the NVP arm who started on the study-recommended regimen, only 20 (2%) stopped the recommended regimen because of concerns of toxicity, and no cases of hypersensitivity were reported.

- The French Perinatal Cohort observed less frequent Grade 2 or higher anemia in 830 infants receiving once-daily NVP versus ZDV prophylaxis in a high-resource setting.41

- In IMPAACT P1115, infants at high risk of HIV acquisition were given NVP twice daily as part of a three-drug presumptive HIV therapy approach; NVP was dosed as 6 mg/kg twice daily for term neonates (≥37 weeks gestational age) or 4 mg/kg twice daily for 1 week and 6 mg/kg twice daily thereafter for preterm neonates (34 to <37 weeks gestational age).21 Among 438 neonates enrolled, 389 (89%) were born at term; 36 were subsequently found to have in utero HIV infection. Division of AIDS (DAIDS) Grade 3 or 4 adverse events that were classified as at least possibly related to ARVs were reported in 30 infants (7%; 95% CI, 5–10) but did not lead to cessation of NVP in any cases; neutropenia (25 neonates [6%]) and anemia (six neonates [1%]) were the most commonly reported toxicities.

Abacavir

Data on the use of ABC in HIV-exposed neonates are limited, but suggest it is well tolerated. In a metanalysis and population PK model that included data from three separate PK trials with a total of 45 infants aged <3 months and born to women with HIV, no adverse events of Grade 3 or greater were attributed to ABC.86 At this time, the Panels suggest using ABC in neonates as an alternative to ZDV in rare situations and only after negative HLA-B*5701 allele testing.

Raltegravir

The primary toxicity of concern with the use of RAL in the neonatal period has been the potential increase in bilirubin levels, but at recommended dosing, RAL appears safe. RAL is metabolized by uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A1, the same enzyme responsible for the elimination of bilirubin; UGT enzyme activity is low at birth, and RAL elimination is prolonged in neonates. In addition, RAL binds to albumin, raising concern that the displacement of bilirubin could lead to hyperbilirubinemia. However, in vitro studies suggested RAL would be safe at the drug exposures achieved for treatment.87 IMPAACT P1110, the single-arm regulatory Phase 1/2 trial that established dosing for RAL, evaluated safety in 52 infants of 34 weeks gestational age and older; no adverse events were attributed to RAL, and no bilirubin levels exceeded 16 mg/dL.88

Combination ARV Regimens

Combination ARV regimens are associated with elevated risk of toxicity compared to single agents, but the three-drug regimens currently recommended for presumptive HIV therapy in neonates (e.g., NVP/ZDV/3TC or RAL/ZDV/3TC) appear very safe when used for 6 or fewer weeks. Early studies of two and three-drug regimens used as prophylaxis suggested that hematologic and mitochondrial toxicity is more common than with exposure to a single NRTI.89-93 However, more recent studies provide data about the safety of the ARV regimen that is currently recommended for presumptive HIV therapy, suggesting it is generally well tolerated, but does confer an increased risk of anemia.

- In IMPAACT P1115, 438 infants of at least 34 weeks gestational age at high risk of HIV acquisition initiated NVP plus 2 NRTIs (ZDV + 3TC in 96%) within 48 hours of life and continued until in utero infection was excluded by HIV DNA testing at birth (a median of 13 days).21 Grade 3 or 4 adverse events at least possibly related to ARVs occurred in 30 (7%) of 438 infants, with neutropenia (25 [6%]) and anemia (6 [1%]) being the most common. Toxicity led to the permanent discontinuation of ZDV in nine (2%) of 438 participants (four found to have in utero HIV, and five without) with neutropenia and anemia being the primary reasons for discontinuation; no other ARVs were permanently discontinued because of toxicity.

- A prospective cohort study in Thailand reported a greater proportion of infants receiving ZDV/3TC/NVP for 6 weeks experienced Grade 2 anemia (38%) at 1 month compared to infants receiving ZDV alone (21%, P = 0.007).94 However, the risk of Grade 3 anemia was lower and similar between arms at 9.2% versus 10.2%, respectively (P = 0.81). Hemoglobin levels recovered by 2 months, at which time there was no difference between the arms. No differences in neutropenia or hepatotoxicity between the groups were observed.

- A retrospective study described outcomes of 148 Canadian infants at high risk of HIV transmission treated with three drugs for 6 weeks including ARV based on NVP (40%), nelfinavir (50%), and LPV/r (5%); all together, infants receiving combination regimens had lower hemoglobin levels than infants who received ZDV alone over 6 months, but no difference was seen between the subgroup receiving NVP-based treatment compared to ZDV alone.32

Generalizability of Available Safety Data

A number of considerations affect the generalizability of the safety data reviewed here to current patient populations.

- The majority of trials included were completed at a time when mothers of infants receiving prophylaxis were not receiving ART. It is possible that ARVs passed through breast milk could add to toxicity in infants also receiving prophylaxis during breastfeeding. Current data suggest that only clinically insignificant, small amounts of approved ARVs enter the breast milk, but this hypothetical possibility must be considered for new agents. See Safety of Antiretroviral Drugs During Breastfeeding in Infant Feeding for Individuals With HIV in the United States for more details.

- This section focused on the risk of severe (Grade 3 or 4) adverse events; most trials did not report the frequencies of lower-grade toxicities. Please see the DAIDS reference tables for more information.95

- The overall rate of adverse events was high in many of the trials. For example, in IMPAACT 1077BF, approximately 35% of infants in both arms experienced Grade 3 adverse events or death, a rate much higher than experienced in settings with more health care resources.65 The high rate of events unrelated to study drugs overall may reflect the limited health care resources in the settings in sub-Saharan Africa. However, some data suggest that the normal value ranges developed in the United States may not be applicable in other settings or countries.96,97 As a result, it is difficult to extrapolate the individual risk of events for an infant in settings that differ from the trials. However, the possibility of an added risk of adverse events from agents can still be evaluated by comparing arms in randomized trials.

- This section focuses on agents and approaches that are currently recommended. Safety data about approaches that are no longer recommended (e.g., NVP plus ZDV) can be found in archived guidelines.

- Additional information about ARV toxicity can be found in the Pediatric Antiretroviral Guidelines (see Appendix A: Pediatric Antiretroviral Drug Information); however, data summarized there are generally from clinical trials and other studies of children with HIV, in whom the coadministration of other ARVs and comorbidities may also have contributed to toxicity.

Infants With HIV Infection

When infant HIV testing returns a positive HIV NAT result, the Pediatric Antiretroviral Guidelines recommend rapid initiation of ART (defined as initiating ART immediately or within days of HIV diagnosis) without waiting for a confirmatory test, given the low likelihood of a false‑positive HIV NAT (see When to Initiate Antiretroviral Treatment in Children with HIV Infection and Diagnosis of HIV Infection in Infants and Children). ART should be discontinued if subsequent negative NAT testing excludes the presence of HIV infection. What to Start in the Pediatric Antiretroviral Guidelines provides recommendations about initial ART for infants and children with HIV, including those who are receiving presumptive HIV therapy or other ARV prophylaxis at the time of diagnosis.

References

- Mandelbrot L, Tubiana R, Le Chenadec J, et al. No perinatal HIV-1 transmission from women with effective antiretroviral therapy starting before conception. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(11):1715-25. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26197844.

- Sibiude J, Le Chenadec J, Mandelbrot L, et al. Update of perinatal human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmission in France: zero transmission for 5482 mothers on continuous antiretroviral therapy from conception and with undetectable viral load at delivery. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76(3):e590-e598. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36037040.

- Jovaisas E, Koch MA, Schafer A, et al. LAV/HTLV-III in 20-week fetus. Lancet. 1985;2(8464):1129. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2865600.

- Lewis SH, Reynolds-Kohler C, Fox HE, et al. HIV-1 in trophoblastic and villous Hofbauer cells, and haematological precursors in eight-week fetuses. Lancet. 1990;335(8689):565-8. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1689792.

- Sprecher S, Soumenkoff G, Puissant F, et al. Vertical transmission of HIV in 15-week fetus. Lancet. 1986;2(8501):288-9. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2874312.

- Brossard Y, Aubin JT, Mandelbrot L, et al. Frequency of early in utero HIV-1 infection: a blind DNA polymerase chain reaction study on 100 fetal thymuses. AIDS. 1995;9(4):359-66. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7794540.

- Rouzioux C, Costagliola D, Burgard M, et al. Estimated timing of mother-to-child human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) transmission by use of a Markov model. The HIV Infection in Newborns French Collaborative Study Group. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142(12):1330-7. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7503054.

- Townsend CL, Cortina-Borja M, Peckham CS, et al. Low rates of mother-to-child transmission of HIV following effective pregnancy interventions in the United Kingdom and Ireland, 2000–2006. AIDS. 2008;22(8):973-81. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18453857.

- Kourtis AP, Lee FK, Abrams EJ, et al. Mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1: timing and implications for prevention. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6(11):726-32. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17067921.

- Wade NA, Birkhead GS, Warren BL, et al. Abbreviated regimens of zidovudine prophylaxis and perinatal transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(20):1409-14. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9811915.

- Van Rompay KK, Otsyula MG, Marthas ML, et al. Immediate zidovudine treatment protects simian immunodeficiency virus-infected newborn macaques against rapid onset of AIDS. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39(1):125-31. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7695293.

- Tsai CC, Follis KE, Sabo A, et al. Prevention of SIV infection in macaques by (R)-9-(2-phosphonylmethoxypropyl)adenine. Science. 1995;270(5239):1197-9. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7502044.

- Bottiger D, Johansson NG, Samuelsson B, et al. Prevention of simian immunodeficiency virus, SIVsm, or HIV-2 infection in cynomolgus monkeys by pre- and postexposure administration of BEA-005. AIDS. 1997;11(2):157-62. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9030361.

- Nielsen-Saines K, Watts DH, Veloso VG, et al. Three postpartum antiretroviral regimens to prevent intrapartum HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(25):2368-79. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22716975.

- Dunn DT, Brandt CD, Krivine A, et al. The sensitivity of HIV-1 DNA polymerase chain reaction in the neonatal period and the relative contributions of intra-uterine and intra-partum transmission. AIDS. 1995;9(9):F7-11. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8527070.

- Mofenson LM, Lambert JS, Stiehm ER, et al. Risk factors for perinatal transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in women treated with zidovudine. Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study 185 Team. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(6):385-93. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10432323.

- Garcia PM, Kalish LA, Pitt J, et al. Maternal levels of plasma human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA and the risk of perinatal transmission. Women and Infants Transmission Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(6):394-402. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10432324.

- Cooper ER, Charurat M, Mofenson L, et al. Combination antiretroviral strategies for the treatment of pregnant HIV-1-infected women and prevention of perinatal HIV-1 transmission. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;29(5):484-94. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11981365.

- Petra Study Team. Efficacy of three short-course regimens of zidovudine and lamivudine in preventing early and late transmission of HIV-1 from mother to child in Tanzania, South Africa, and Uganda (Petra study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359(9313):1178-86. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11955535.

- Lallemant M, Jourdain G, Le Coeur S, et al. A trial of shortened zidovudine regimens to prevent mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Perinatal HIV prevention trial (Thailand) investigators. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(14):982-91. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11018164.

- Ruel TD, Capparelli EV, Tierney C, et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of early nevirapine-based antiretroviral therapy for neonates at high risk for perinatal HIV infection: a phase 1/2 proof of concept study. Lancet HIV. 2021;8(3):e149-e157. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33242457.

- Persaud D, Ray SC, Kajdas J, et al. Slow human immunodeficiency virus type 1 evolution in viral reservoirs in infants treated with effective antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2007;23(3):381-90. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17411371.

- Luzuriaga K, Tabak B, Garber M, et al. HIV type 1 (HIV-1) proviral reservoirs decay continuously under sustained virologic control in HIV-1-infected children who received early treatment. J Infect Dis. 2014;210(10):1529-38. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24850788.

- Persaud D, Patel K, Karalius B, et al. Influence of age at virologic control on peripheral blood human immunodeficiency virus reservoir size and serostatus in perinatally infected adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(12):1138-46. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25286283.